Social Determinants of Health: Not Just Another Hot Topic

Take a minute and rate your own health on a scale of 1-10, with 10 as your best possible health.

Now think about why you chose your rating. In your mind, what factors determine your health?

The purpose of this exercise is not to make you feel especially bad or good about your health. The purpose is to better understand a concept as important and complicated as “health.”

For instance, many people will think of these factors when they think of health:

- sleep

- pain

- exercise

- mood

- diet

- illnesses

- genes

- physical and mental (dis)abilities

- energy

- pain

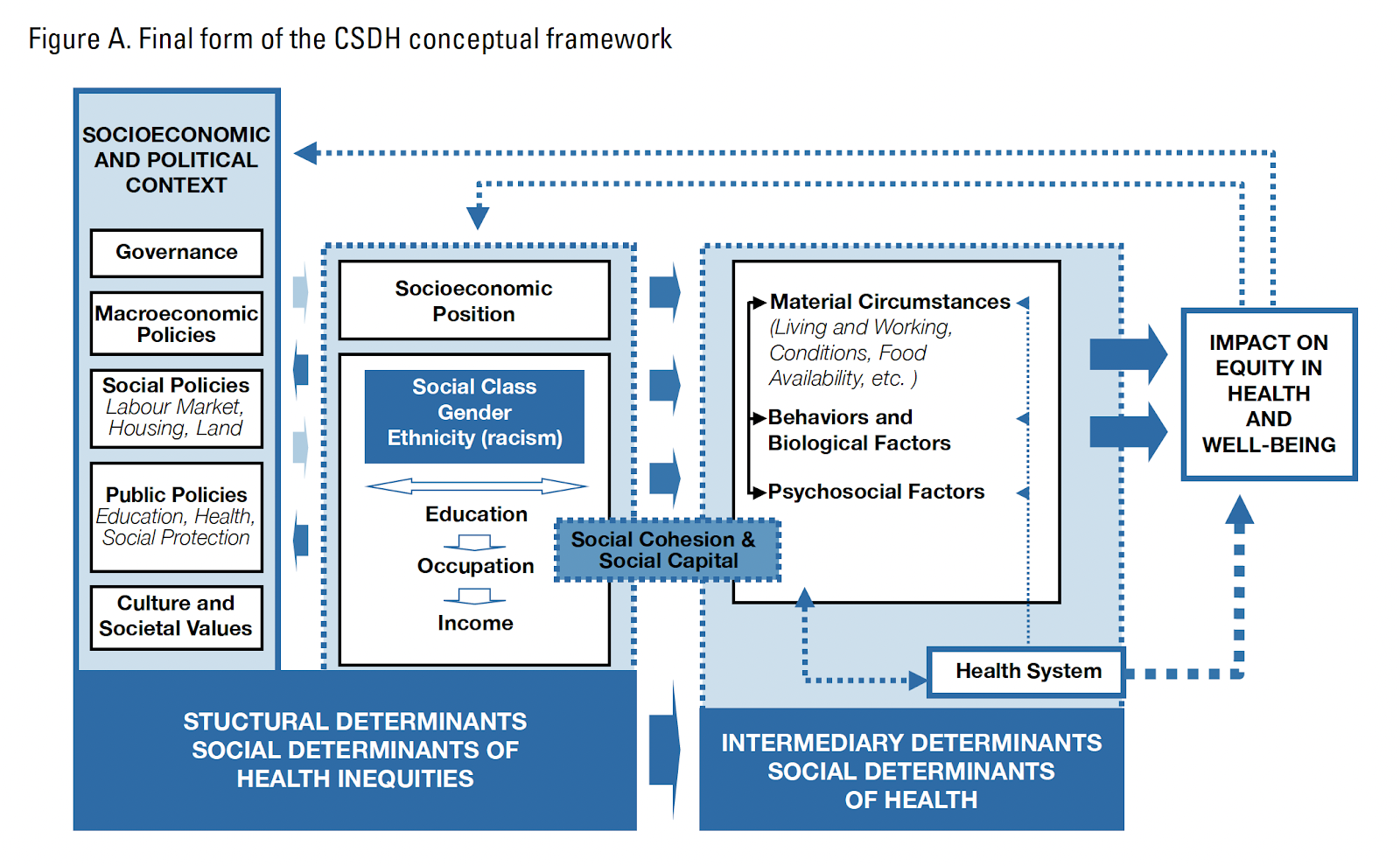

However, according to one health framework—Social Determinants of Health (SDH)—these factors are just a small slice of the overall pie. The listed factors are what the World Health Organization’s Committee on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) framework calls “behaviors and biological factors.” But as the CSDH figure shows, there is a lot more to health:

This figure is rather complicated, and it comes primarily from the field of public health. However, psychologists—especially counseling psychologists—are increasingly recognizing the importance of SDH to their own work as therapists, researchers, teachers, advocates, and more.

In other words, psychologists are increasingly seeing physical and mental health as inextricably connected, and we are seeing health equity—the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health—as a goal for us as psychologists, not just for those in other fields like public health and medicine.

Let’s briefly break down the CSDH framework and what it means for psychologists. The CSDH framework proposes structural determinants (the left half of the figure) and intermediary determinants (the right half of the figure).

- Structural determinants include the socioeconomic and political context, which produces group- and individual-level differences in socioeconomic position and access to power and resources.

-

Intermediary determinants are more downstream than structural determinants, operate more directly on health outcomes, and include material circumstances, psychosocial circumstances, behavioral and/or biological factors, and the health system.

Take income and material circumstances as an example:

- Income is a structural determinant, because the structure of society—the socioeconomic and political context—shapes the distribution of income among groups of people. For instance, in the United States, a low minimum wage, high cost of living, and other causes of income inequality are some factors that contribute to unequal access to a middle-class income.

- Material circumstances are intermediary determinants, such that income determines material circumstances (e.g., whether you can live in a neighborhood with low levels of community violence, whether you can afford enough healthy food) and material circumstances determine health (e.g., inadequate nutrition and the stress of community violence are two of many things that lead to worse mental and physical health outcomes).

Importantly, it is the structure of society (e.g., the patriarchy, White supremacy) that distributes differential power and access to resources based on certain characteristics, such asgender identity and race/ethnicity.

Think back to your list of factors that determined how you rated your health on a scale of 1 to 10.

- Did you include income, gender, ethnicity, food security, and neighborhood violence on your list?

-

What about many other relevant CSDH factors not discussed here, such as occupational status, education and health care access, social support, and more?

Many people like to think their health is entirely or largely within their control. As long as they start or continue eating well, exercising, going to the doctor, and practicing self-care to decrease stress, they’ll be fine. However, the CSDH framework illustrates that many health determinants can only be impacted by systemic change, such as policies to tackle systemic racism, sexism, and other -isms, and to improve health care access and quality, housing and labor markets, and more. As just one example, increased income via increased Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits has been associated with lower disability rates among elderly Americans.

The American Psychological Association (APA) describes counseling psychology as being “culturally informed,” focusing on “prevention and education as well as amelioration,” and “addressing individuals as well as the systems or contexts in which they function.” These emphases on prevention, systems, and culture call for counseling psychologists to take a view of health as broad and complex as the one in the CSDH framework. To borrow the groundwater metaphor from teachings on structural racism, how can you prevent many fish from dying or getting sick by looking at individual fish in individual lakes? You must look to the broader cultures and systems and clean up the groundwater that connects all lakes and fish.

So, what can you do to incorporate social determinants of health into your work?

If you see clients:

If you teach:

If you conduct research:

If you engage in advocacy, or want to start:

As hard as individual change is, systemic change can be even harder. But with commitment to clear health frameworks that include systems, not just individuals, we have an easier path to walk on the way to health equity.

Bio: Ayla Goktan (she/her) will be entering her third year in the University of Louisville Counseling Psychology PhD program in Fall 2023. As a Turkish-American heterosexual cisgender woman who grew up middle class, she attempts to incorporate multiculturalism in work. Ayla is interested in doing health psychology research, including with social determinants of health frameworks, and working in medical settings, such as the Kentucky HIV/AIDS Care Coordinator Program and Norton Children’s Hospital. She is a member of the American Psychological Association (including APAGS and Division 17) and the Kentucky Psychological Association (KPA). In her free time, she runs, writes poetry, plays the flute, and spends time with her friends, family, and partner.

Posted on: November 19, 2023

|